Bananas start my day. I eat one almost every morning and seldom leave a grocery store without a fresh bunch. But the familiar yellow Cavendish banana is a threatened fruit, succumbing to Panama Disease in several parts of the world and facing extinction like the Gros Michel banana so popular 50 years ago.

I heard about this threat a few years ago but the details were vague. My reaction was disbelief. How could a common fruit available at the corner store for 79 cents per pound be in peril? But it is, and it has been for decades. Dan Koeppel’s new book, Banana: The Fate of the Fruit That Changed the World [LibraryThing / WorldCat], explains it all and delivers a few surprises, too.

I heard about this threat a few years ago but the details were vague. My reaction was disbelief. How could a common fruit available at the corner store for 79 cents per pound be in peril? But it is, and it has been for decades. Dan Koeppel’s new book, Banana: The Fate of the Fruit That Changed the World [LibraryThing / WorldCat], explains it all and delivers a few surprises, too.

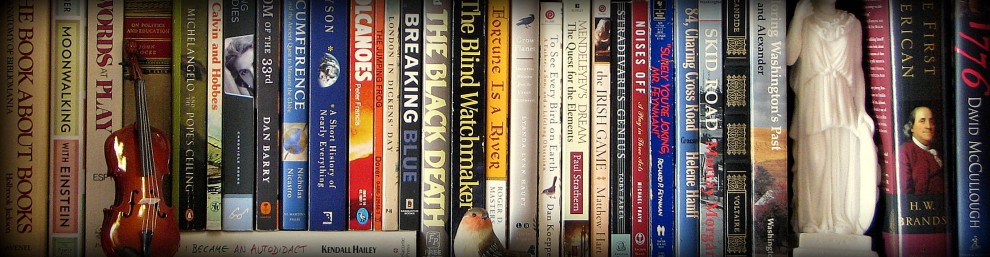

Koeppel, the author of To See Every Bird on Earth (a book I enjoyed two years ago and reviewed here), takes us on a history of the banana with all its innovations, corruption, and place in our culture.

- Innovations: Transporting a tropical fruit to northern markets before rotting brought about the beginnings of the modern fruit industry.

- Corruption: There’s a reason ‘banana republic’ is a derisive term. The one or two largest banana companies operate in the shadow of terribly shameful histories.

- Culture: I need only mention vaudevillians slipping on a peel, “Yes, We Have No Bananas”, and that oval blue sticker.

Between the tragic tales of oppression in Central America and curious banana miscellany, Koeppel returns again and again to the research and strategies involved in the nearly century-long battle to save the Cavendish banana crop. The banana is eaten by more people around the world than apples and oranges combined, he says. It’s more critical to their diets, too.

It’s also more vulnerable. Every seedless Cavendish is a clone of its mother plant, difficult to cultivate and susceptible to disease. Panama Disease, Black Sigatoka, and several other plant-choking maladies have already ravaged plantations across Asia and Africa. It’s only a matter of time before it threatens Central America, devastating not only the fruit but the people and economies dependent on the banana. Banana republics have never had it easy.

I eat a Cavendish daily. I like red bananas, too. Lately I’ve been cooking plantains. I’d like to try some of the other varieties Koeppel mentions, but most are unavailable in the United States due to economic reasons (i.e. not enough supply; not enough demand). Disease-resistant bananas might prove to be the solution to the Cavendish’s problems, but, ironically, such engineered marvels would be unavailable in most foreign markets that prohibit genetically-modified foods.

There’s no easy solution. The banana is a delicious fruit surrounded by problems.