Musicians are constantly toying with us. They roll a melody up and down a musical rollercoaster. They take us on unexpected sidetracks. They bounce themes from one instrument to another like kids playing hackey sack. And sometimes they smuggle other tunes (themes or motifs) into their melodies to knock us off our guard. Somehow we keep up with their games, catching and interpreting hundreds of minor cues per second, and reconstruct their art as emotion. Joy. Sadness. Loss. Hope. Love.

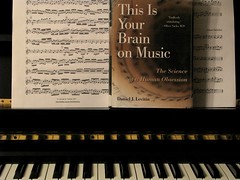

Daniel Levitin carries on wonderful discussions like these in This is Your Brain on Music, a book I picked up because of the title but stuck with because of the subject. Levitin is a former studio musician and sound engineer who worked with many of the top pop acts of the 70s, 80s, and 90s, but followed an academic calling when a fascination for the complex interplay between sound and the human brain caught his attention. The result is a unique study of how the human brain reacts to music. And how cool is it that the same guy can tell you about a dinner he had with Francis Crick (the co-discoverer of DNA) in one chapter and about hanging out at home with Joni Mitchell (blues singer of “Both Sides Now”) in the next?

Daniel Levitin carries on wonderful discussions like these in This is Your Brain on Music, a book I picked up because of the title but stuck with because of the subject. Levitin is a former studio musician and sound engineer who worked with many of the top pop acts of the 70s, 80s, and 90s, but followed an academic calling when a fascination for the complex interplay between sound and the human brain caught his attention. The result is a unique study of how the human brain reacts to music. And how cool is it that the same guy can tell you about a dinner he had with Francis Crick (the co-discoverer of DNA) in one chapter and about hanging out at home with Joni Mitchell (blues singer of “Both Sides Now”) in the next?

Not only do we remember the words and tune to Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the USA”, but we can automatically mimic the places his voice becomes gravelly. Why? What happens to the brain at 115 decibels that makes so many people prefer music cranked up to that volume? Why do so many people hate fingernails on a chalkboard? How on earth can we recognize a song like the Eagles’ “Hotel California” after listening to it for only a tenth of a second, or recorded by a dreary orchestra and played through a cheap elevator speaker? Why do some songs, rhythms, or instruments instill feelings in us so easily? How do they prompt memories? Why is music so enjoyable? And why do we get “ear worms” — 15 second song snippets that we can’t seem to get our minds to stop playing over and over? And over.

Levitin wrote his narrative in a way that respected both the music and the latest science research. He’s a musician, after all, with a deep appreciation for the art. And his neuroscience isn’t all mathematics. Music is filled with math and theory, but Levitin doesn’t dwell on it. He runs through a ‘Music Theory 101’ review in the first two chapters so you know what an octave is, the differences between pitch, tempo, and timbre, and what role chords play. It’s complicated in spots, but it’s just to get you up to speed so he could talk to you later using the right vocabulary.

Late in the book, Levitin delves into the invention of music and the evolution of the human brain. He went over my head several times, but whenever he started to lose me in brain/music jargon he pulled me right back with examples from songs everyone would know — ubiquitous songs from classic rock, country, jazz, or folk: Chuck Berry’s “Roll Over Beethoven”, Dave Brubeck’s “Take Five”, Rogers & Hammerstein’s “My Favorite Things”, Sting’s “Every Breath You Take”, the Beatles “Yesterday”.

Many of the songs he mentioned were already on my iPod. I listened to them anew with an ear out for the twists he suggested. I still felt the same emotion from the music, but the excursions into music theory and neuroscience added just a bit more depth to the experience. Music is a wonderful thing and the human brain is astounding. This was the first book I’ve read that covered both topics at the same time.