“Life will not be contained. Life breaks free. It expands to new territories, crashes through barriers… Life finds a way.”

When Ian Malcolm (played by Jeff Goldblum in the movie Jurassic Park) said those words, he was foreshadowing the disastrous end of a human-designed biological theme park. But he would have been just as accurate describing the natural world as a whole.  Time and time again, humans thought they understood what life was and what its limits were. Each time, they have been humbled by a new discovery. For several hundred years, scientists tried to finish their comprehensive lists of earth’s species only to realize they needed more paper.

Time and time again, humans thought they understood what life was and what its limits were. Each time, they have been humbled by a new discovery. For several hundred years, scientists tried to finish their comprehensive lists of earth’s species only to realize they needed more paper.

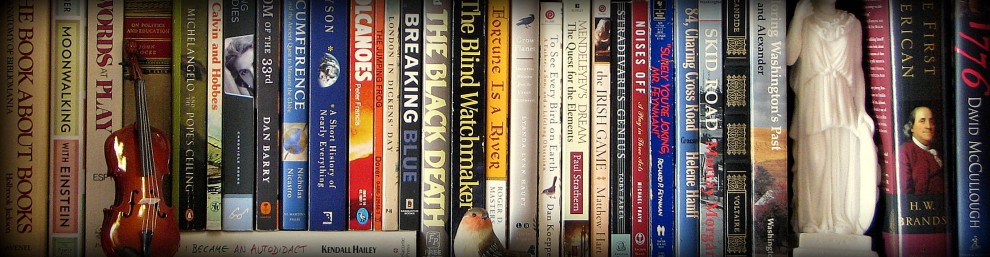

Every Living Thing [LibraryThing / WorldCat] by Rob Dunn is one of those books that blows your mind: What you know about life isn’t one-tenth of what you don’t know. I’m not referring simply to something as newsworthy as finding a new monkey (as the book’s subtitle mentions). We thought we had all monkeys documented and studied, but a new one was found recently. If a new monkey can still be found, what else is still out there? There are likely whole ecosystems no one has yet imagined.

Dunn begins in a remote area of Bolivia where inhabitants know the local species quite well. They are more familiar with their animals and insects than most of us in the industrialized, “educated” world know of our own. The variety of the world’s megafauna is greater than you might expect.

From there, Dunn plunges us into history. He follows Linneaus, an 18th century biologist who attempted to list all the animals in the world on a brief sojourn into the Swedish countryside, but came to realize there were many more species than he (or anyone) anticipated. Leeuwenhoek startled the scientific world when he found countless “invisible” creatures swimming in water tucked under his new microscope. His studies revealed an environment on a previously unknown scale.

Within our own lifetimes, science had established guidelines for which environments were sterile — too hostile for anything to survive. But researchers have had to repeatedly erase and reassess. Entire classes of life have been found in places considered too acidic, too hot, too cold, too pressurized, or too exposed to radiation. Life has not only been found in caustic sulfur deposits and boiling undersea vents, but it has thrived in those places. Living organisms have been found in rock miles beneath our feet. Nanobacteria have been found living all around us at atomic scales smaller than a strand of our DNA.

We humans mostly concern ourselves with an extremely thin zone at the earth’s surface. We know the worms and vegetables a few feet down. We see the animals and trees near us or slightly overhead. But the abundance we see is nothing compared to what we don’t see. Dunn’s book expands that view. Each chapter leaves you with a perspective of life much larger than you considered the chapter before.

There appear to be no inhospitable environments; no region devoid of living creatures; no dead zones. If one is suspected, scientists should look more carefully. “Life finds a way.”