When I was a kid, every day was packed with ten times the activities I’d dream of doing now. Most of it was spontaneous, like finding out what kind of dog was barking on the next block. All of it was important, like finding out what the school looked like upside down. I remember knowing who lived in each house on the street; big impromptu neighborhood games of hide-and-seek with kids I assumed had simply materialized for the occasion; exploring the woods behind Rob’s house and with him preparing for the eagerly anticipated pine cone war that never came against Mark and his evil friends. Much of my childhood was spent outdoors. It was also, in retrospect, largely comical. It was certainly eventful. [That’s me in the cape, by the way.]

When I was a kid, every day was packed with ten times the activities I’d dream of doing now. Most of it was spontaneous, like finding out what kind of dog was barking on the next block. All of it was important, like finding out what the school looked like upside down. I remember knowing who lived in each house on the street; big impromptu neighborhood games of hide-and-seek with kids I assumed had simply materialized for the occasion; exploring the woods behind Rob’s house and with him preparing for the eagerly anticipated pine cone war that never came against Mark and his evil friends. Much of my childhood was spent outdoors. It was also, in retrospect, largely comical. It was certainly eventful. [That’s me in the cape, by the way.]

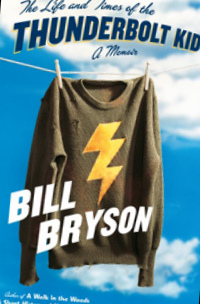

Better than any childhood memoir I’ve read, The Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid by Bill Bryson captures childhood with the spirit and mischievousness of a real kid. It’s nostalgia for a boy’s world in the 1950s long before video games and scary strangers kept kids boarded up in their homes on sunny days.

This is the ninth Bryson book I’ve read. He is the author of, among other titles, A Walk in the Woods, In a Sunburned Country, and A Short History of Nearly Everything — all great reads on very diverse topics. In Thunderbolt Kid, he blends wickedly entertaining childhood recollections with his gift of laugh-out-loud humor writing.

This is the ninth Bryson book I’ve read. He is the author of, among other titles, A Walk in the Woods, In a Sunburned Country, and A Short History of Nearly Everything — all great reads on very diverse topics. In Thunderbolt Kid, he blends wickedly entertaining childhood recollections with his gift of laugh-out-loud humor writing.

As with any Bryson book, the writing is top notch. My favorite passage vividly explains how he “knew more things in the first ten years” of his life than at any time since. As a kid, for instance, he knew how to cross rooms without touching the floor, the contents of every closet in the house, the taste of non-food objects, and the feeling of a wide variety of pains. Back then, he said, a whole morning could pass just fixing the laces on your sneakers. I could relate to every thing on his list.

Bryson also tells stories (most of them universally shared, I’m sure) about being fascinated by a kid with a nosebleed, his love of comic books and television, and finding fun outdoors. “Kids were always outdoors,” he writes. He would run into them everywhere. By the thousands. He and his friends tried to get free candy from the theater vending machine and “for the first time in history the inside of a vending machine was exposed to children’s view.” He ached to be near Mary O’Leary — not understanding why exactly, just knowing that it should be so: “She smelled of vanilla — vanilla and fresh grass — and was soft and clean and painfully pretty.”

Although the Iowa he grew up in sounds a lot like “Leave it to Beaver”, Bryson knew that things were not ideal for everyone. Race relations in America were anything but good in the 1950s, but on the Des Moines side of the cornfield, at least, Iowans got along. Blacks were few, but not disliked. Blacks and whites tended to live in separate neighborhoods but shopped, played sports, and went to the movies in the same places. One of his friends was gay. That friend, in fact, helped him sneak into the stripper tent at the state fair. He also had a smart friend who used his ample brain power for some really stupid things.

I’m a generation younger than Bryson, but his childhood was mine, too. I remember the neighborhood full of kids, and long summer days with nothing — and everything — to do. My Mary O’Leary was named Diane and my brainy friend was Eric. Bryson’s details differed from mine, but he got the feeling right. This was a delightful read.