“Of course I’m happy just to get through the morning without being pelted with rocks,” Jim Malusa wrote the day after repeated attacks from “forty-pound children with stones” — children who reminded him of those in The Lord of the Flies. The experience, along with warnings given by others, left him with the nagging feeling that “pedaling a bike through Djibouti is a ridiculous way to suffer voluntarily.”

But his Djibouti trip wasn’t all suffering. He saw remarkable landscapes and met interesting people who generously took him into their homes and shared meals and conversation.

But his Djibouti trip wasn’t all suffering. He saw remarkable landscapes and met interesting people who generously took him into their homes and shared meals and conversation.

Djibouti was part of an unusual quest for Malusa. All adventurers seek novelty. They plunge into an unexplored wilderness; traverse a continent on foot or an ocean in a rowboat; hand-climb an untouched rock formation or glide solo around the world in a sailboat … or a balloon. Mountaineers collect summits. The Seven Summits, a well-known term in mountaineering circles, describes the quest to ascend the highest peaks on all seven continents.

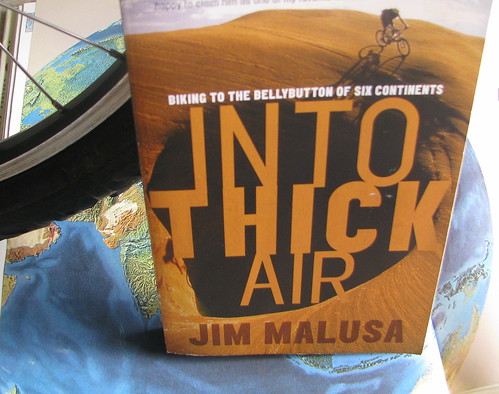

Jim Malusa did the opposite. He set out to reach the lowest point on each continent. The belly buttons. The Six Pits. But his book, Into Thick Air, is more a travelogue than an adventurer struggling against the odds. Instead of facing frostbite or possible missteps on high peaks, he sought “some place warm. Some place I can ride my bike.”

He might have reached his goal easily enough. Almost all the world’s low points are accessible. Tourists drive to the Dead Sea every day. People live in Death Valley. But Malusa specifically planned his bike routes to steer him into interesting places and increase his encounters with a variety of people. The belly buttons were not so much goals to achieve as they were devices to interact with people in places seldom visited by Westerners. Riding a slow-moving bicycle gave him the opportunity to soak up the scenery, stop in every town, and meet the locals in lands unaccustomed to such outside attention. In this way, the chapters in his book roll along.

Riding alone and exposed on a bicycle in unfamiliar territory, of course, made him feel vulnerable, too. He feared the Djibouti kids with rocks, but also bandits in South America, and animals in Australia. He camped outside in the cold, rode in searing desert heat, faced strong Patagonian winds, and fussed with border patrol bureaucracy: “You cannot bring a bicycle into Jordan.”

His greatest successes involved people. Malusa managed to strike up conversations with people living lives and holding perspectives far different than his own. They seemed drawn to him, too. Many had never left their native lands and were eager to know about the greater world or to travel as he was doing. Everyone seemed willing to chat or, in the case of two men in Argentina, stop their truck suddenly to tackle an armadillo.

At times I bristled at the curious routes Malusa planned (biking to the Dead Sea by way of Cairo?), but his observant and very descriptive writing made the biking travelogue enjoyable. And although he’s not as consistently funny as Bill Bryson (author of A Walk in the Woods and Notes from a Small Island among others), Malusa’s humor shows up regularly. This was an enjoyable book.

By the way: The book title is an obvious counterplay to Jon Krakauer’s tragic adventure classic Into Thin Air: thin air up at Everest, thick air down in Death Valley.