Bird books seem to my biggest new indulgence this year. No fewer than seven of them have followed me home (so far) in the last 12 months. [I’ve reviewed several here; search my blog for “birds” to retrieve them.] As a group, these books have been a delight. Birders and the little flitting critters they follow make for enjoyable reading.

Bird books seem to my biggest new indulgence this year. No fewer than seven of them have followed me home (so far) in the last 12 months. [I’ve reviewed several here; search my blog for “birds” to retrieve them.] As a group, these books have been a delight. Birders and the little flitting critters they follow make for enjoyable reading.

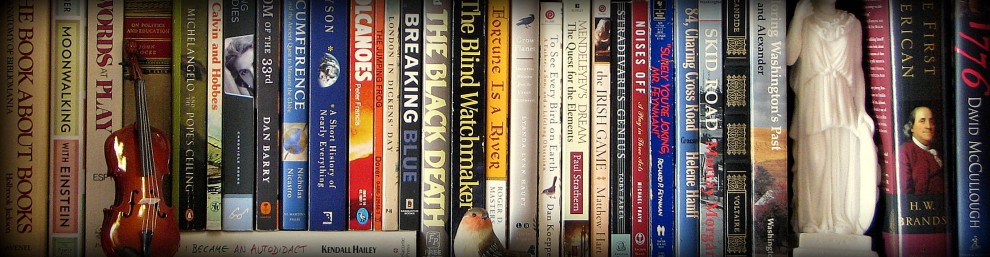

My latest find, however, is a feast for the eyes. Paul Bannick, a fellow Washingtonian, has assembled a marvelous collection of photographs in The Owl and the Woodpecker [LibraryThing / WorldCat]. Both birds mentioned in the title are “indicator” species, suggesting the health of the local environment. The woodpecker, with its industrious cavity-drilling behavior, is a “keystone” species, as well. They inadvertently build homes for other animals with each hole they excavate.

Setting out to find and photograph all 19 owls and 22 woodpeckers native to North America, Bannick wandered into the field with a couple of high-powered digital cameras, a personal bird blind, and infinite patience. Within the book’s text, he discusses the habitat and behavior of each bird he sought. Close study enabled him to read the environment and ultimately find every species. After finding a bird, Bannick deployed his patience. With the eye of a photographer, he considered light, angles, and probable roosting and nesting sites. Then he planned (and waited) for the pictures that appear in the book.

What pictures they are! You might marvel at the colorful clarity of two Yellow-shafted Northern Flickers peering from a nest on page 139, take in the color of a Gila Woodpecker sipping from a saguaro on page 104, or admire the confident flight of a Short-eared Owl on page 97. Most of Bannick’s woodpecker photos reveal activity: working over a tree, feeding their young, or storing acorns. His owls show either show their impressive wings in flight or their captivating eyes, perpetually watching. Page after page, those attentive eyes seem to reinforce the most memorable line of text in the book for me: “I use stealth to approach … but every time I have found a Northern Spotted Owl, it was already looking at me.” Through Bannick’s camera, it looks directly at you, too.

Bannick’s writing is tedious at times, but each new page offers a fresh new image. In the back of the book, there’s a nine page guide to all the species, along with a “calls and drumming” CD to help identify the birds by sound.

Addendum: I met Bannick in Seattle the day after I finished reading the book. His images and descriptions were still so fresh in my mind that his slide presentation made me feel like I was thumbing through the book a second time. I didn’t mind at all.