I devoured maps as a kid. The endless intersecting lines within an atlas could entertain me for an hour at a time, and I’d recreate the the curves and jagged edges with paper and pencil. The United States map is a natural puzzle, with pieces rubbing against each other along straight edges, curves, river-led curls, and strange little appendages.

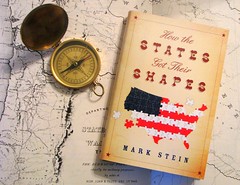

But what made those unique shapes? We’ve all heard “54 40 or Fight” (a border that didn’t stick) and the Mason-Dixon Line (which did), but how did all the other peculiar borders come into being? What kid hasn’t wondered why there’s a big corner chunk missing from Utah, why Oklahoma has a thin panhandle, why Vermont and New Hampshire make up a diagonally divided near-rectangle, why states in the Midwest are stacked in columns, why Minnesota pokes a finger into Canada, or why Michigan’s Upper Peninsula wouldn’t be better off as part of Wisconsin? Questions like these arise every time a child solves a 50-state board puzzle, but, in my case anyway, the answers didn’t show up before my curiosity faded. Or so I thought. While reading Mark Stein’s How the States Got Their Shapes [LibraryThing / WorldCat] I was surprised that my curiosity about these things hadn’t disappeared. It was reawakened, border after quirky border: “Oh yeah, what about that?”

But what made those unique shapes? We’ve all heard “54 40 or Fight” (a border that didn’t stick) and the Mason-Dixon Line (which did), but how did all the other peculiar borders come into being? What kid hasn’t wondered why there’s a big corner chunk missing from Utah, why Oklahoma has a thin panhandle, why Vermont and New Hampshire make up a diagonally divided near-rectangle, why states in the Midwest are stacked in columns, why Minnesota pokes a finger into Canada, or why Michigan’s Upper Peninsula wouldn’t be better off as part of Wisconsin? Questions like these arise every time a child solves a 50-state board puzzle, but, in my case anyway, the answers didn’t show up before my curiosity faded. Or so I thought. While reading Mark Stein’s How the States Got Their Shapes [LibraryThing / WorldCat] I was surprised that my curiosity about these things hadn’t disappeared. It was reawakened, border after quirky border: “Oh yeah, what about that?”

Chapters in Stein’s book are doled out to every state and arranged alphabetically — an organization better suited for reference or browsing than reading. But I’m not shy. I came up with a plan. After reading the two introductions, I started in the alphabetical middle — Maine — and worked my way through the country geographically, one region at a time. The quirks of the map were more plentiful than I remembered: Delaware has a semicircular northern border; Connecticut once laid claim to parts of Ohio; and Missouri can thank an earthquake and a single landowner for its “boot heel.” We notice the four straight sides of Colorado and Wyoming because they’re the exceptions. The more commonplace rules include Pennsylvania’s index tab on the Lake Erie shore, the southern kink in Washington’s otherwise straight eastern border, the curious notch in northern Connecticut or the snipped southwestern corner of Massachusetts.

Many of the border lines derived from the needs of river navigation and access. Many others were planned by Congress — but involving generations of Congressmen with slightly different strategies. Most involved compromise. Some were clearly mistakes. Surveyors’ gaffes are preserved in the outlines of Tennessee, Idaho, and Oklahoma, to name only a few. Poor Maryland lost every border dispute that came its way, was carved up by all its neighbors, and today has a curious mix of straight and meandering lines that, at one point, leaves the state less than 3 miles wide. Even island-bound Hawaii has a western boundary tale to tell.

The book omitted a story close to me, however. Point Roberts, shown here in a Google map, is a tiny peninsula a few hours from my home in Washington State. It’s American land but can be reached only by boat or a drive through Canada. When the international boundary was set at 49 degrees north latitude, treaty negotiators didn’t notice the thin finger of land lazily drooping a couple miles across the line. The treaty specified the latitude, though, and Point Roberts had the nerve to park just south of it. It’s an American “island” on the Canadian mainland. I’ve been there on my bike, in fact, and rode the gravel line to the survey marker at its western end.

The book omitted a story close to me, however. Point Roberts, shown here in a Google map, is a tiny peninsula a few hours from my home in Washington State. It’s American land but can be reached only by boat or a drive through Canada. When the international boundary was set at 49 degrees north latitude, treaty negotiators didn’t notice the thin finger of land lazily drooping a couple miles across the line. The treaty specified the latitude, though, and Point Roberts had the nerve to park just south of it. It’s an American “island” on the Canadian mainland. I’ve been there on my bike, in fact, and rode the gravel line to the survey marker at its western end.

The book is quite repetitive, but that can’t be helped. One state’s eastern border is another state’s western frontier that you encounter in another chapter. If you’re willing to skim familiar material, however, the stories in How the States Got Their Shapes are fascinating, and the maps are plentiful. I thoroughly enjoyed the meander through the book and the travel through history.